The Hawai’i depicted on tv and in film, on people’s Instagram accounts during and post-vacation, in advertisements and commercials—that Hawai’i does not exist. Hawai’i is wildness and scent and taste, smoke and lava and sweat and the pounding of poi, Hawai’i is the wai, the water, thrusting through valleys, Hawai’i is a collision of flavor born of the cultures that arrived there over the past centuries.

I’m the first to admit that the Hawai’i I grew up in, daughter of recovering hippies on Maui, was just one whitewashed version of the state. My upbringing never encompassed the full scope of Hawai’i’s richness, the density of its flavor palate, the power of its communities and intersectional identities. Sure, we grew liliko’i and papaya and apple bananas, but I didn’t taste many of Hawai’i’s most distinctive local foods (like lomi salmon, squid luau, and Spam) until I was in my thirties—thanks to chef and photographer Alana Kysar.

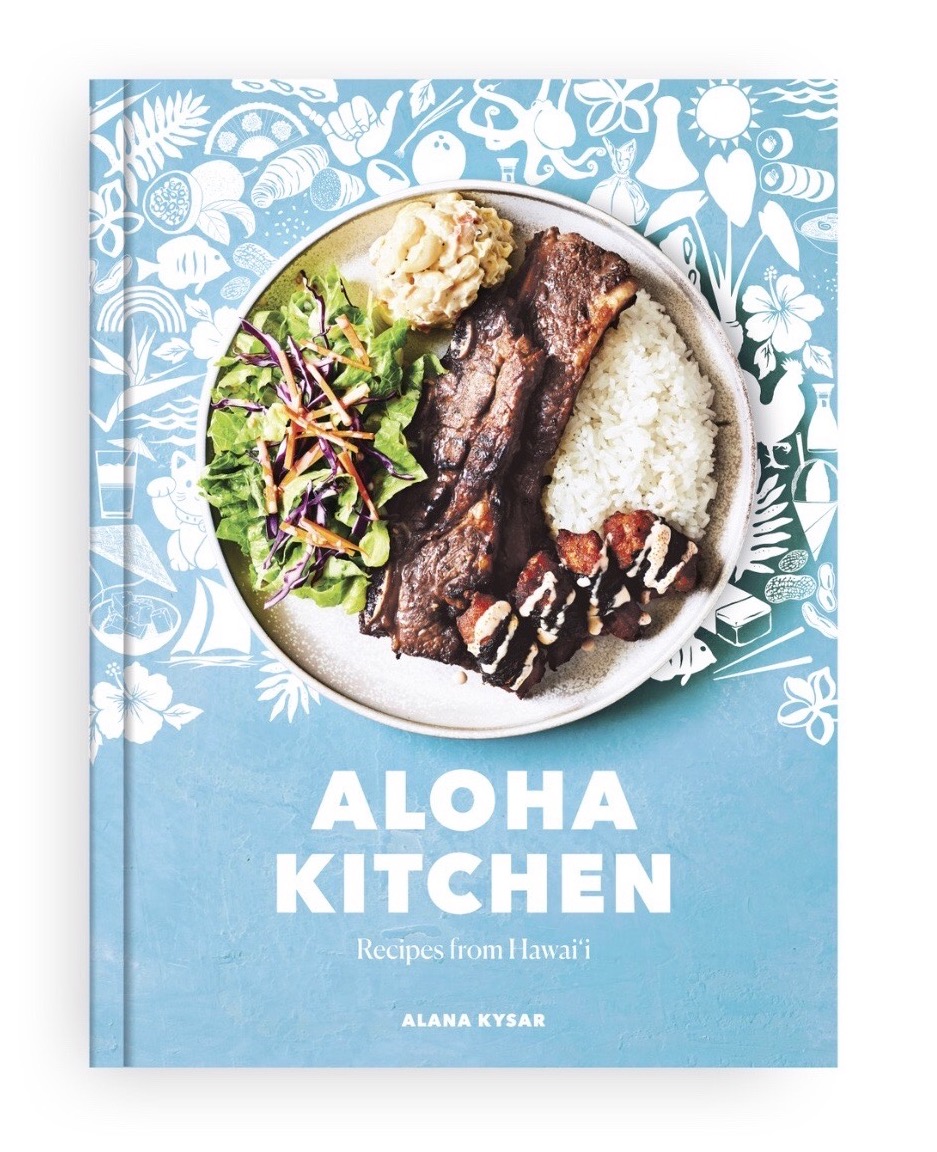

Which brings me to today—a world-altering day, in my opinion. Today Alana’s book Aloha Kitchen: Recipes from Hawai’i is born. Alana—also a daughter of the slopes of Haleakalā, where I grew up—has crafted a work of encyclopedic value in its ability to catalog and represent the diverse culinary voices that comprise local Hawai’i cuisine. A book like this one does not exist for Hawai’i, and let me be the first to tell you that you must own it.

The book opens with stunning vistas of Hawai’i’s backyards and shorelines, a rallying call to the local lifestyle its pages so effortlessly embody. Alana describes:

“The aloha spirit, as defined by a state statute, ‘is the coordination of mind and heart within each person. It brings each person to the self. Each person must think and emote good feelings to others. Aloha must be extended with no obligation in return, and to live aloha, you must ‘hear what is not said, see what cannot be seen, and know the unknowable.’ … This way of life—placing the aloha spirit at the core of relationships and actions—is what truly makes Hawai’i a special place.”

Aloha Kitchen carries the potency of this charge to live, forge relationships, and cook with such intention. We discover Alana’s Japanese American and European heritage even as we delve into the Native Hawaiian, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Portuguese, Filipino, and Western influences that shape the food that fills local plates statewide. With a deft and generous history lesson, Alana illuminates the distinction between local food (the food resulting from an amalgamation of the influences above) and Native Hawaiian cuisine—while forever abolishing the incorrect fetishization of “Hawaiian” food as anything containing ham or pineapple (shudder).

Aloha Kitchen introduces 85 recipes spanning the dining table and kitchen, from pantry staples like pickled mango, hurricane popcorn, and li hing mui (a salty-sweet-tangy delicacy you can’t wait to have in your life, trust me) to a wide range of pūpū (appetizers), meats and seafood, noodles (hello saimin!), and luscious desserts (liliko’i chiffon pie forever, please). While the book is certainly meat-heavy, many of the recipes can be easily adapted to your diet—as I did with these soy-glazed tofu musubi.

With the author’s permission, I subbed out Hawai’i’s iconic Spam for tofu. The recipe worked beautifully, with just an additional sprinkle of salt on the tofu as it fried. Though I attempted to use short-grain brown rice here, I don’t recommend it—you really need short-grain white rice to properly stick together for musubi munching.

Not only does Aloha Kitchen: Recipes from Hawai’i deliver a visceral experience of the islands through photographs, food, and stories, it also provides a much-needed reminder of the culinary legacy of colonialism and plantation life in Hawai’i, past and present. And, with requisite aloha, the book affirms the power food has to give voice to native cultures and transcend prejudice, creating a place for us all to thrive—and eat ‘ono grinds (delicious food) along the way.

Musubi molds can be purchased from Amazon, along with your copy of Aloha Kitchen: Recipes from Hawai’i by Alana Kysar, from Ten Speed Press.

SOY-GLAZED TOFU MUSUBI.

Ingredients

- 2 tablespoons soy sauce (shoyu)

- 2 tablespoons light brown sugar

- 1/2 teaspoon mirin (optional)

- 1-2 teaspoons neutral oil

- ~14 ounces tofu, drained and cut horizontally into 8 slices

- sea salt to taste

- 3 sheets roasted sushi nori, cut into thirds crosswise

- 2 teaspoons furikake

- 5-6 cups cooked short-grain white rice

- fresh cilantro (optional) to garnish

- pickled mango or daikon (optional) to garnish, recipes in Aloha Kitchen

Instructions

- In a small bowl, whisk the soy sauce, brown sugar, and mirin (if using) together. Set aside.

- Lightly coat the bottom of a large skillet with the oil and heat over medium heat. Sprinkle each tofu slice with a bit of sea salt, and fry the tofu slices until evenly browned and crispy, 3-5 minutes on each side. Turn the heat to low for the last minute of cooking, then turn off the heat. Pour in the soy mixture and quickly turn the tofu slices to evenly coat them. The mixture will cook down in less than a minute, so don't walk away for this part or your glaze may burn. Immediately transfer the tofu slices, with glaze, to a plate.

- Place a strip of nori, rough side up, on a cutting board or clean work surface. Place the musubi maker mold over it, in the middle, then place a slice of tofu in the mold. Sprinkle 1/4 teaspoon furikake over the tofu, then fill the mold with a generous mound of rice. Press the rice firmly with the musubi maker press until it is 3/4 to 1 inch thick, adding more rice as necessary. Use the press to hold the rice down with one hand and pull the mold upward to unmold the musubi with your other hand. Wrap the nori and the tofu-rice stack, bringing both ends of the strip to the middle, folding one over the other, and flipping it over so the seam is down and the tofu is facing up. Repeat with remaining ingredients. Serve immediately, with an extra sprinkle of furikake, cilantro, and pickle as desired, or wrap with plastic wrap to take with you on the go.